Devilishly good

First heard of Tom Cunanan, Genevieve Villamora, and Nick Pimentel's Bad Saint from Bon Appetit Magazine's rave piece back in August of last year, declaring the little cubbyhole the second best new restaurant in America.

Filipino? Second best in the country? Aside from a chauvinistic kneejerk reaction (Only second best?) I was skeptical. Then almost three months later the Washington Post's Tom Sietsema harumphed about the Michelin Guide's inclusion of the eatery as one of D.C.'s nineteen Bib Gourmand restaurants of 2016--places of good value for 'dining off the clock,' or cheap eats. The food critic opined that the Guide's definition of what's cheap isn't the same as ours (basically two courses and dessert or a glass of wine for $40, minus tax and tip). "The place deserves better," he declared, describing the twenty-four seat no-reservations establishment as a "gem, as gracious as it is luscious," and adding "Outside of a home, I doubt if there's better Filipino cooking anywhere in the country." In November the New York Times' Pete Wells wrote "I have now spent roughly twice as many hours standing on the sidewalk outside Bad Saint as I have spent inside eating its Filipino food" which sounded like the prelude to a complaint so I braced myself: turns out he considered the waiting part of the experience.

Officially curious now, so we drove into the city--well, into the outskirts, taking the Metrorail into the city--one cold March Sunday afternoon, walking down Columbia Heights' 11th Street till we arrived at a small building with a large graffiti vividly spraypainted into one side

an intricately wrought metal giraffe at the corner

an art gallery/theater/community center complete with mini bamboo grove right next door. The place itself didn't look like much: glass doors next to wood-framed windows with bamboo blinds. Only thing distinguished it from the showier establishments up and down the block: the line of people waiting patiently for the doors to open.

The establishment's name incidentally is taken from a community named Saint Malo that once stood in Louisiana, the first-ever Filipino community in the United States; the folks there were called 'Manilamen' or Tagalas, had no police (they governed themselves) and paid no taxes (an oversight, presumably). The town was wiped out by hurricane in 1915, the people assimilated by nearby New Orleans.

They weren't kidding about the wait. We arrived at 3 PM, decided to walk around; came back fifteen minutes later and there was already a line of ten. Someone had brought a chair (he was the smartest of us); everyone else passed the time either in conversation or on their smartphones.

So what to talk about within earshot of intimidatingly well-dressed presumably high-cultured D.C. folks? The readability of Jane Austen of course. Naturally we were putting on a show ("We read books! Classics too!") and I doubt if we fooled anyone but it was my companion's literature assignment anyway, who alas hated Persuasion with a passion ("Why use thirty words to say something I could rephrase in five?"). I insisted that Austen unlike Dickens (as Nabokov once put it) needs a little context, a little introducing, a lot of patience, but is ultimately rewarding for her precise woman-from-Mars observations of 19th century English society. I liked Austen, something which surprised my companion (who knows my tastes in film and literature) quite a bit.

Had to call it a draw when Ms. Villamora unlocked the door and started welcoming guests. Inside the hot heart of the establishment hooded cooking ranges flamed and billowed smoke

the cooks banging woks on iron grates when they weren't sprinting back and forth

surrounding them was a tiled counter/bar on which customers were seated, and surrounding them were long wood shelves lining the walls (there were at most four freestanding tables, able to seat at most four people).

Space was at a premium and used three-dimensionally: the tiled counter had tubular-framed shelving that reached almost to the ceiling, on which they stored bottles and glasses for the bar, one shelf housing plates, another functioning as a sort of shrine for pictures of employees' kids, wives, parents, friends, pets.

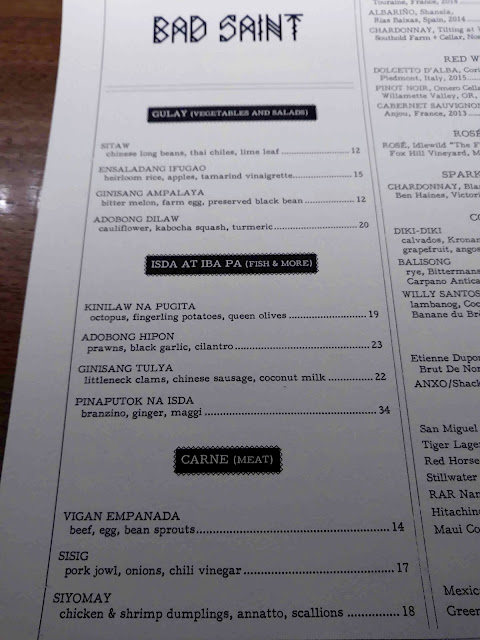

The menu seemed simple enough; it changes I think every so often--the famed ukoy (shredded sweet potato and tiny shrimp patted into large pancakes and deep fried) wasn't available, nor was the beloved kaldaretang kordero (stewed lamb necks) or the fairly infamous (because it sounds so disgusting on paper) dinuguan (pork meat and innards in a black blood stew).

We ordered and waited; the second wait didn't seem long--we were too busy looking around at the teeming tinkling place, not exactly noisy but humming with energy. Washing my hands at the bathroom was startled to see it wallpapered with blown-up posters of Filipino punk-rock bands, reportedly part of Nick Pimentel's collection (couldn't recognize the names--either I've been too long out of touch with the scene or Pimentel's collection is too esoteric).

The first major dish was adobong hipon--prawns in black garlic cilantro soy and vinegar, the soy and vinegar emphasizing the seawater sweetness of the fresh prawns, the blackened garlic (basically garlic heated gently for a time till Maillard reaction turns its sugars toasty dark) and cilantro adding funky earthy turf to the dish's surf. Highlight of the dish of course are the prawn heads--suck on the bright red fat inside and you'll feel a rush from the richness (basically shrimp butter with the depth of organ meat) spreading throughout your tongue.

As palate cleanser: the kinilaw na pugita, a salad of raw octopus cooked gently not by heat but vinegar, with fingerling potatoes. The octopus was clean and tender; the fingerlings gently mimicked the shellfish's texture, bringing a taste of soil to the seafood, the dish's profile elevated by briny olives, crunchy red and if I can trust my taste buds inatsarang (pickled) onions

Next came the Vigan empanada--deep-fried pasties filled with ground beef bean sprouts chopped boiled egg, served with a dip of onion and spicy vinegar. The meat had a faintly sweet & spicy flavor, the flaky crust and chopped egg acted as starchy cushion, the dip cutting the filling's richness nicely.

Highlight of the meal: classic sisig, pig face cut up and served on a hot plate topped with green onions and bird's eye chilies, a raw egg cooking gently in the residual heat. The chopped pork was a world of textures (crispy skin chewy tendon tender flesh) and flavors (sweet meat bitterburnt trimmings salty fat) sizzling on hot iron, the chilies and green onion acting as punctuation, the warm egg yolk a touch of over-the-top decadence.

Followed by the gorgeous pinaputok na isda--steamed whole branzino (a European seabass) skewered with a stalk of lemongrass, stuffed with ginger and leaves (I'm thinking from the bittertart flavor it's mustard greens) flavored with Maggi seasoning (a Swiss soysaucelike condiment with a powerful umami hit).

The meal ended with a complementary suman sa latik, or sticky rice in a darkly rich coconut caramel--only the suman is actually a slice of plantain not rice, wrapped in banana leaf to look like the classic dessert.

Interesting to wonder how the meal--and Bad Saint as a whole--connects to Filipino cuisine. Much of this is a superb rendition of a Filipino dinner, much an interesting variation thereof: the enselada for example has no real equivalent in traditional cooking (A rice salad?); the sugpo's garlic makes for a sweeter--balsamic, almost--adobo, classic Filipino with an unusual ingredient, the chopped black cloves a dramatic contrast to the sugpo's vibrant orange. I've tasted enough kinilaw, from fish to shrimp to scallops to (deliciously) goat to consider octopus not much of a stretch, but fingerlings? Intriguing, with a texture and flavor that's both complement (delicate, tender) and contrast (shellfish meat, root vegetable).

Vigan empanada is traditionally stuffed with longanisa, a vinegary garlicky chorizolike sausage, and shredded green papaya; the ground beef used here is more like asado (barbecued pork) than sausage meat, the bean sprouts a less common addition (to counteract the sweetened meat?). Sisig is usually flavored with calamansi, a sweet little lime that tastes like a cross between a mandarin and a lemon that you squeeze into a ramekin with soy sauce; here the dish came with another serving of their spicy oniony garlicky vinegar. Familiar enough to spark memories of home, startling enough that you're thinking about the difference.

The branzino--never seen fish served that way, spiked with a lemongrass stem, but the showmanship works, the flavor fabulous. The suman was a creative little detail--thought I'd been served the usual till I put a forkful in my mouth; wasn't sure about the slight tartness of fruit (admittedly starchy fruit) in place of glutinous rice, but after a few chews the mouthful made itself at home with the thick sweet latik.

Figure the owners are taking off on an idea Ferran Adria once expressed in an interview: he goes on all kinds of wild and creative tangents but his inspiration and constant touchstone are the classics of Spanish cooking, the goal being to evoke the powerful feelings of those dishes but from a different direction, using different techniques and ingredients. Same I submit with Bad Saint: a bowl of adobo on rice, a fish steamed in banana leaves, a simple kinilaw of fish in chopped onions and vinegar--it's home cooking approached from a different direction, made special but not too special that you'd feel uncomfortable, as if having to dress formally for an opera. There's a casual precision here that isn't too far off from what Austen (so recently in my mind) does on the printed page--a chef from Mars so to speak both making commentary and putting his mark on Filipino cuisine.

Part of the experience and no small part was the feeling you got of being a casual guest in someone's fashionably designed living room, offered plates off a constantly buzzing kitchen. Amanda our server was all warm smiles, eager to answer questions and explain the dishes; the food itself came in relatively brief intervals (compared to that wait outside) where each succeeding bite contrasted and changed the pace and hue and theme of the meal (sea and land; meat and vegetable; raw and cooked; steamed and fried) from one dish to the next (enselada followed by adobong sugpo followed by an empanada; a break with the kinilaw; sisig and then pinaputok na branzino in a kind of one-two combination; finally the 'suman' "--oh by the way there's this sweet little thing--").

Is it worth going for Filipinos? All too familiar with our attitude ("Why pay $40 before taxes or tips and wait two hours for something we can get at home?") but I'd like to point out that we sometimes wait patiently for hours for home meals, knowing the results will be worth it. And taking off from Adria, it's an experiment pointing at and inspired by a cuisine that is itself continually changing innovating growing--what our food is capable of, given state-of-the-art techniques and ingredients. Not necessarily better just different, by turns tribute variation and extension of what our mothers and grandmothers cooked for us back home.

As for folks who haven't tried Filipino or don't know a Filipino who'll invite you to sit at their table (believe me we will, and out of a sense of affectionate mischief we will offer the dinuguan): go. It's possibly the time of your life, up to and including the long wait in that Columbia Heights neighborhood (where I hope to settle the question of Austen once and for all someday).

Bad Saint: 3226 11th Street NW

Washington DC 20010

Mon, Wed, Thurs, Sun: 5:30-10PM

Fri, Sat: 5:30-11PM

Tues: Closed

Contact: info@badsaintdc.com

No phone number as you see; they don't accept reservation and don't seat parties larger than four

First published in Businessworld 5.4.17

Rarely order alcohol, but for this occasion I had a glass of lambanog, an often sweet and powerful (around 40 proof) coconut wine.

No comments:

Post a Comment